Immediately, I Love Him

He produced so many delicate and empathetic pictures of ladies, and a few of the most civic-minded masterworks of the twentieth century.

Once I was a youngster, Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica,” that colossal antiwar portray rendered in newspaper tones of black and grey, was on mortgage to the Museum of Fashionable Artwork. The artist had despatched it to New York earlier than World Struggle II to safeguard it from Francisco Franco, the dictator who ended democracy in Picasso’s native Spain.

“Guernica” stayed right here for greater than 4 many years, and rising up beneath its spell enlarged my sense of what artwork could possibly be. Artwork, it appeared, was not in regards to the pursuit of refinement and social polish however an encounter with the sort of uncooked, screaming emotion adolescents haven’t any hassle greedy.

I remained a Picasso worshiper, whilst buddies embellished their dorm rooms with posters by Matisse — blankly elegant pictures of all-blue nudes scrubbed of any element. They enchanted however they lacked the earthy potato-life that sprang from so many Picasso pictures. His pencil traces pushed by area and curved in opposition to gravity like some new sort of wind-resistant plant that botanists had but to call.

It isn’t massively cool to profess a love for Picasso today. His standing as the best of all fashionable artists, which was taken as an article of religion for a lot of the twentieth century, has worn skinny in a #MeToo world. A part of the issue is that his self-advertised picture as a sexual conqueror, a Don Juan with a paintbrush, now not charms. As we all know from an ever-growing shelf of biographies and memoirs, he could possibly be an unrepentant bully. He mistreated his quite a few wives and mistresses, ensnaring them in a sadistic two-step of seduction and abandonment in violation of all requirements of decency.

As we ponder the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s demise, on April 8, and the cornucopia of 40-plus museum exhibitions that may commemorate him, in New York and throughout Europe, I discover myself pulled between disapproval of the person and a critic’s adoration of his artwork. And, as within the case of critics who’ve cringed on the offending views of Ernest Hemingway, Richard Wagner and T.S. Eliot, the artwork love wins out. I can not agree with feminist critics who write off Picasso as a pseudo-master whose work has been overrated and artificially propped up by the patriarchy.

Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937) seen by guests on the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid. The portray is a logo of the horrible struggling that warfare inflicts.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Emilio Parra Doiztua for The New York Occasions

One of many nice ironies surrounding his life is {that a} man who behaved so callously towards girls produced so many delicate and empathetic pictures of them, to not point out a few of the most civic-minded masterworks of the twentieth century. That is what Picasso’s detractors — like Hannah Gadsby, the Australian comic and Picasso basher, who will assist curate a Picasso present on the Brooklyn Museum opening on June 2 — usually miss.

If there’s an argument to be made in 2023 that he must be ignored on the idea of his misbehavior, there’s one other to be made for the necessity to look deeply at his artwork once more. Since his demise the rise of feminism has offered a lens by which to rethink his work and particularly his illustration of ladies. And there’s a lot we’re simply starting to note.

For starters can we please retire the oft-cited plaint that he decreased girls to intercourse objects? Girls have been the dominant topic of his artwork and he seen them as sources of vulnerability and power. They seem in a variety of personas and moods. He painted girls who have been intellectuals and artists. Girls who engaged with the world or turned away from it in dreamy reverie. Girls with two profiles and vertically stacked eyes, icons of emotional complexity. In 1937, he painted the anguished girls of “Guernica” — noble messengers alerting the world to the horrors of the Spanish Civil Struggle.

Has every other visible artist left us with such a vivid pantheon of feminine characters? Paul Cézanne, in contrast, rendered his spouse Hortense as a extreme matron who seems much less animated than the apples in his nonetheless lifes. Edgar Degas was much less within the inside lives of his ballerina-subjects than within the animal awkwardness of their our bodies and the pleasure of glimpsing them from behind. Amedeo Modigliani’s stylized portraits make his a whole lot of feminine topics appear like a part of an prolonged household whose members have a genetic predisposition for lengthy faces and giraffe necks.

Picasso, in contrast, introduced the load of lived expertise into his work, even when he was tethered to archetypal topics. He can pretty be known as the foremost painter of mom and kids of the twentieth century. One in all my favorite-ever work is “The Mom,” on the St. Louis Artwork Museum, during which a 30-ish lady seems in bony profile, hurrying into city, beneath a cloudy, green-smudged sky. As she grips the hand of her chubby toddler (who chomps distractedly on an apple) and carries her second youngster on her shoulder, she exemplifies motherhood purged of the standard Renaissance-style bliss. Right here, as a substitute, is a girl who will go to the ends of the earth for her kids and isn’t anticipating anybody’s thanks.

“The Mom” (1901), an early portray by Picasso, exhibits a view of motherhood purged of Renaissance idealization. Here’s a lady who will go to the ends of the earth for her kids.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through Saint Louis Artwork Museum

In “Gertrude Stein” (1905-6), Picasso depicts the American expatriate author’s immense skills in her hulking presence.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork

And within the pantheon of Picasso superwomen, let’s not overlook Gertrude Stein, the American expatriate author who took a shine to the younger Spaniard. Stein, who was 15 years older than him, traipsed often up the steep hill in Montmartre to pose in his studio within the fabled Bateau-Lavoir. His well-known portrait of her, on the Metropolitan Museum, brilliantly transforms her further 30 kilos and linebacker shoulders into an indication of her immensity as a author. Wearing her regular brown corduroy coat, she is as monumental as any of the biblical sibyls gazing down from the Sistine ceiling.

For years we targeted on Picasso as Mr. Modernism, the audacious avant-gardist who co-founded Cubism within the years earlier than World Struggle I. Working with Georges Braque, he shattered the single-point perspective that had prevailed in portray because the Renaissance. As a substitute of replicating literal actuality, he sought, within the twisting twister of Analytic Cubism (1910-12) and later within the wider and sunnier planes of Artificial Cubism, to dismantle the method of seeing, to seize the little shifts of notion that happen in time as you ponder any sight.

His fantasy has been burnished by his prodigious output — he produced an estimated 13,500 work, along with astounding portions of drawings, prints, sculptures and ceramics — in addition to his embrace of contradictory types. He veered between reverse poles of abstraction and realism, between the gaunt, poetic figures of his Blue Interval and the zaftig matrons of his Rose Interval, between the paper-lightness of his wildly creative collages and the bulbous tonnage of his sculpted bronze heads. As Jackson Pollock, his much-younger American admirer, as soon as remarked, “That man missed nothing!”

Once I was in school, finding out artwork historical past, I used to be taught that Picasso was a Prometheus-like determine who gave the present of inventive fireplace to Pollock and his fellow Summary Expressionists within the war-torn ’40s. However his affect started waning within the early ’60s, when Modernism yielded to Put up-Modernism, with its emphasis on pastiche and irony. The brand new artwork god was Marcel Duchamp, an expatriated Frenchman who was residing quietly in Greenwich Village, a wry, cerebral artist-philosopher who claimed to have given up artwork for chess. What’s artwork? Something, Duchamp contended, even a store-bought bottle rack, and his exaltation of discovered objects ultimately turned its personal art-school orthodoxy, main two generations of artists to marginalize portray as passé.

“Bottlerack” by Marcel Duchamp, 1961 model of a 1914 authentic that the artist proclaimed to be a murals and known as a “readymade.”Affiliation Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through Philadelphia Museum of Artwork

Immediately, nonetheless, when so many youthful artists are occupied with their private tales and emotions of social marginalization — whether or not by race, gender or ethnicity — the medium of portray has returned to prominence. And Picasso himself, hyper-conscious of his Andalusian origins and expatriate standing in France, may be seen as a forerunner of the current flip to autobiography in artwork.

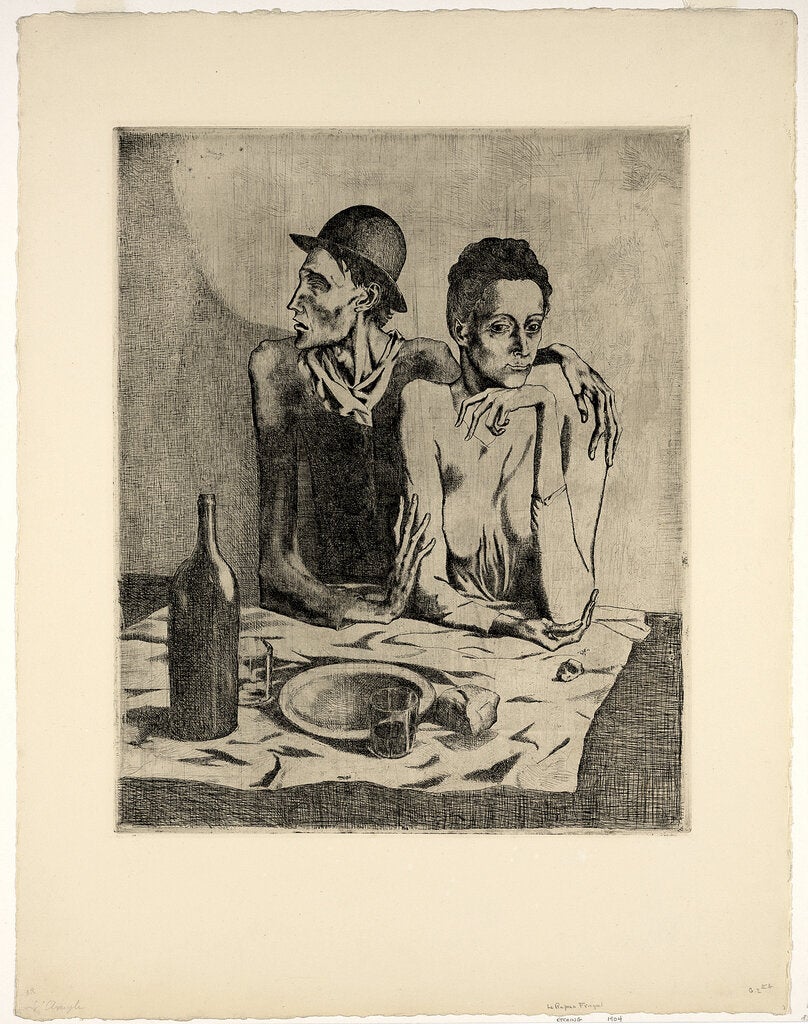

Two new books argue as a lot. Pascal Bonafoux’s “Picasso: The Self-Portraits” is a pretty quantity that brings collectively the artist’s 170 self-portraits in numerous mediums, together with pictures. And in “Picasso the Foreigner,” the French author Annie Cohen-Solal cuts by the standard fluff about Parisian bohemia (goodbye absinthe) and takes us as a substitute north of town, to the archives constructing of the French police. Consulting yellowed paperwork, she tracks the xenophobia that adopted Picasso in his adopted homeland, the place the police branded him an alien. Tellingly, he by no means turned a French citizen, which can partly clarify the temper of disenfranchisement that infuses the early work of his Blue Interval and particularly his scenes of “saltimbanques” or circus performers, like “The Frugal Repast,” his first-ever etching, during which emaciated lovers with spindly El Greco fingers don’t have anything on this world however one another.

Pablo Picasso, “The Frugal Repast” (1904, printed 1913). The etching captures his empathy for socially marginalized, down-and-out folks.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork

One of many important exhibits this yr, “Picasso and El Greco,” opening on the Prado Museum in Madrid on June 13, will take a look at how the younger Picasso was formed by his Sixteenth-century Greek-born predecessor, whose flame-like kinds attraction to everybody’s internal expressionist.

In New York, the Picasso-themed exhibitions shall be modestly scaled. A small however promising present opening Could 12 on the Guggenheim Museum, “Younger Picasso in Paris,” facilities on “Le Moulin de la Galette,” a newly conserved masterwork from the everlasting assortment. Accomplished in 1901, it was amongst Picasso’s first canvases in Paris as a 19-year-old newcomer torn between the realism of the Spanish previous and the unfastened brushwork of French Put up-Impressionism.

I just lately visited the Guggenheim’s conservation lab, the place the portray regarded dazzling. Set at a well-known dance corridor close to the artist’s studio, “Le Moulin de la Galette” offers off a glowy vitality. Picasso clearly delighted within the sight of the dozen or so girls gathered on the corridor — with their vivid crimson lips and rouged cheeks, their fur stoles and lengthy attire, their animated gestures as they whisper to one another, heads pressed collectively. The male figures, in contrast, are complete duds; they’re principally faceless. Within the higher left nook of the portray, three gents in high hats perch on a raised platform, coldly assessing the attractiveness of the ladies.

Picasso’s “Le Moulin de la Galette” (1900) exhibits a dance corridor scene with vibrant lights and girls sitting or standing, whispering with one another. They trace at Picasso’s fascination with feminine figures because the heroes of contemporary life.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s “Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette,” a touchstone of Impressionism, 1876.Musée d’Orsay

The portray recollects earlier French work, particularly Renoir’s “Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette,” a touchstone of Impressionism set within the healthful mild of midafternoon. Picasso’s canvas is extra engaging as a result of it’s set at night time and suffused with a lot radiance, whether or not within the girls’s expressions or within the electrical lights that stretch in a garland throughout the highest of the canvas, tiny blurs of yellow flashing in opposition to the enveloping mist of velvety, Velazquez-like darkness.

The traditional view of the portray holds that the ladies are “dolled-up cocottes,” as John Richardson glibly put it in his biography of Picasso. But it must be stated that the ladies are extra alive than the lads. They trace at Picasso’s fascination with feminine figures because the heroes of contemporary life.

So how might I ever activate Picasso? I received’t. Not ever. He sustained a outstanding depth of feeling as he shifted from the convincing realism of this early work to the splintered shards of Cubism. It was a spectacular leap, and you observed it was pushed by his data that everybody’s life seems to be damaged into items when glimpsed shut up.

Immediately, I Hate Him

We now view his crowning masterpiece “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” by a scrim of unsettling questions.

Please, I urge of you. DO NOT MENTION his title to me.

It was at all times the identical with him. Girls who revered him because the blazing solar round which life revolved invariably suffered the indignity of his womanizing and malice. I keep in mind my shock once I learn years in the past that Françoise Gilot, considered one of his muses, accused him of urgent a lighted cigarette to her cheek throughout an argument, as if to model his seal into her pores and skin.

I’m not suggesting that Picasso’s work be faraway from museums. That might be silly and self-defeating. However wouldn’t it damage to disregard Picasso for the second? It’s simply frequent sense that an artist could cause offense solely so many instances earlier than you start to hunt out extra uplifting firm. There are numerous artists much less acclaimed than Picasso who deserve our consideration. Go see a present by a girl artist right now. The present season in New York occurs to be a bonanza, with main exhibitions by Sarah Sze and Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt) on the Guggenheim, and Cecily Brown on the Met.

Picasso’s offenses transcend his boorish therapy of ladies. He was disrespectful of complete cultures. Requested in 1920 to contribute a number of traces to {a magazine} article on African artwork, he notoriously snapped: “African artwork? By no means heard of it.” It was a stunning assertion from a person who had helped himself to African riches — not pearls and gem stones, however fairly mental property, African concepts and kinds that may show important within the invention of Cubism. He had excitedly visited the Trocadero, the ethnographic museum in Paris whose show circumstances have been filled with ceremonial masks from the Ivory Coast and different colonial booty, artifacts that may assist free a technology of Western artists from the centuries-old obligation to deal with portray as an imitation of nature.

We are going to by no means know who, precisely, created the masks that Picasso borrowed for his “Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907), that crowning masterpiece during which 5 prostitutes rendered in pink tones gaze out from a Barcelona brothel, their angled arms and torsos heralding the tilting area of Cubism. The portray, which lives on the Museum of Fashionable Artwork, is as shut as Picasso ever got here to issuing a manifesto. However right now we view its floor by a scrim of unsettling questions. The 2 figures on the precise are outfitted with West African masks — refined and spiritually laden objects that Picasso yanked out of context and decreased to mere props in a crude sexual fantasy.

Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” from 1907, heralds the radically tilting area of Cubism. The 2 prostitutes on the precise are carrying West African masks.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through The Museum of Fashionable Artwork

Like most critics, I subscribe to rule No. 1 of cultural appreciation: One should separate an artist’s life and work. Artistic endeavors are inevitably made by imperfect human beings. And it doesn’t diminish the inherent integrity of a portray or a sculpture to ponder its maker’s peccadilloes and moral lapses.

However Picasso is totally different, partly as a result of he drew a lot consideration to his personal life, capitalizing on a media trade that had not existed for Degas or Cézanne or different of his predecessors. It’s simple to image him, a brief, compact man with a cannonball head and Svengali eyes, posing for Life journal in his striped Breton sailor’s shirt. He modeled shirtless as nicely, a bare-chested pugilist in boxer shorts, waving a Gauloise cigarette. His work was so explicitly autobiographical that he referred to it as his “diary.” It could possibly be divided, he stated, into seven distinct types, each tethered to considered one of his feminine muses.

By now we really feel like we all know them, beginning with Fernande Olivier, his first muse, an artists’ mannequin whom he immortalized as a doleful presence beneath a black mantilla, as if to emphasise his Spanish origins. Olga Khokhlova, a Russian ballerina born in Ukraine, was his first spouse, her wavy auburn hair pulled again to disclose her porcelain pores and skin in a well-known portrait. They have been nonetheless married when he took up with 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter, an athletic blonde then residing along with her mother and father. She impressed his inordinately prolific “miracle yr” of 1932, which produced such masterworks as “Woman Earlier than A Mirror” and “Le Rêve (The Dream).” She is simple to acknowledge in his work, along with her yellow hair and boneless physique, a tumbling jumble of circles and spheres.

Marie-Thérèse Walter was often known as Picasso’s “golden muse” and her blond hair makes her simple to acknowledge in his work.Apic/Getty Photos

“Woman Earlier than a Mirror” (1932), a Cubist portray by Picasso of Walter considering her reflection, her physique a jumble of circles and orbs.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through The Museum of Fashionable Artwork

In 1935, solely two months after Walter gave delivery to their daughter Maya, Picasso fell in love with Dora Maar, a daring photographer admired by the Surrealists. A darkish magnificence with blue-black hair, she turned the topic of Picasso’s Weeping Girls work, and seems as spiky and jagged as Walters had been fecund and spherical. Maar underwent shock remedy after he left her for Gilot, a painter herself who achieved enduring fame by changing into the primary of Picasso’s muses to stroll out on him, to extricate herself from the Minotaur’s labyrinth-prison. I’ve sometimes noticed Gilot from a distance on the Higher West Aspect of Manhattan, a 101-year-old artist in a crimson coat, out for a day stroll. You rock, Françoise!

Picasso’s “The Weeping Girl” (1937) exhibits his lover Dora Maar weeping right into a handkerchief, her lips trembling.Property of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; through The Museum of Fashionable Artwork

On the threat of piling on, we’d additionally acknowledge Picasso’s dereliction as a father and grandfather. His lovers not less than selected his firm and presumably reaped occasional rewards. His 4 kids, in contrast, by no means signed on for adventures with Pablo — or for his or her eventual abandonment by him. After 1964, when Gilot printed her best-selling “Life with Picasso,” he reportedly refused to just accept a go to or perhaps a telephone name from their kids, Claude and Paloma. The saddest life was certainly that of his grandson Pablito, who, at age 24, was turned away from Picasso’s funeral by his widow, Jacqueline Roque; he went house and dedicated suicide by consuming bleach.

And but. Whereas accounts of his unsavory personal life proliferated over time — there was, as an example, Arianna Huffington’s “Picasso: Creator and Destroyer” (1988), and “Picasso: My Grandfather” (2001) by Pablito’s sister, Marina Picasso — they didn’t tarnish his picture. Quite, it appears, they enhanced his fantasy as a person of supersized passions. Within the fashionable creativeness, Picasso’s masculine bravado, like van Gogh’s insanity, was taken as a perverse affirmation of his inventive genius. It had no discernible impact on the art-world equipment that has stored his work on perpetual view at main museums and top-flight galleries, and stored his public sale costs sky-high.

Françoise Gilot with Pablo Picasso and his nephew Javier Vilató, captured on the seaside in Golfe-Juan, France, August 1948, by Robert Capa.Robert Capa/Worldwide Middle of Images/Magnum Pictures

Because of this, I really feel indebted to the #MeToo motion, which has led us to collectively rethink varieties of abuse that have been as soon as ignored or laughed off. Within the 50 years since Picasso’s demise, it goes with out saying that nothing has modified about him or his work. However we’ve modified dramatically as a society; we consider within the rightness of calling out the conduct of people that assume their privileged standing quantities to a license to abuse. It’s too late to demand penance from the lifeless. However it isn’t too late to demand a modicum of decency from the residing.

How ought to we really feel about Picasso? There isn’t any unified reply, simply as there aren’t any unities of type in his work. Isn’t that what made him so radical? He understood the impossibility of seeing issues in a single fastened method, even comparatively easy issues, like a mandolin or a bowl of oranges on a tabletop. As a substitute he confirmed us how a number of views, superimposed, can coexist in the identical portray, on the identical second, in the identical head.

The act of wanting, he appeared to say, doesn’t produce a static and unchanging image, however fixed fluctuations in notion. So maybe it’s becoming that no artist has been the topic of extra shifts in viewpoints than he himself. I really like him. I hate him. Picasso has left me ceaselessly divided.

Supply: NY Times